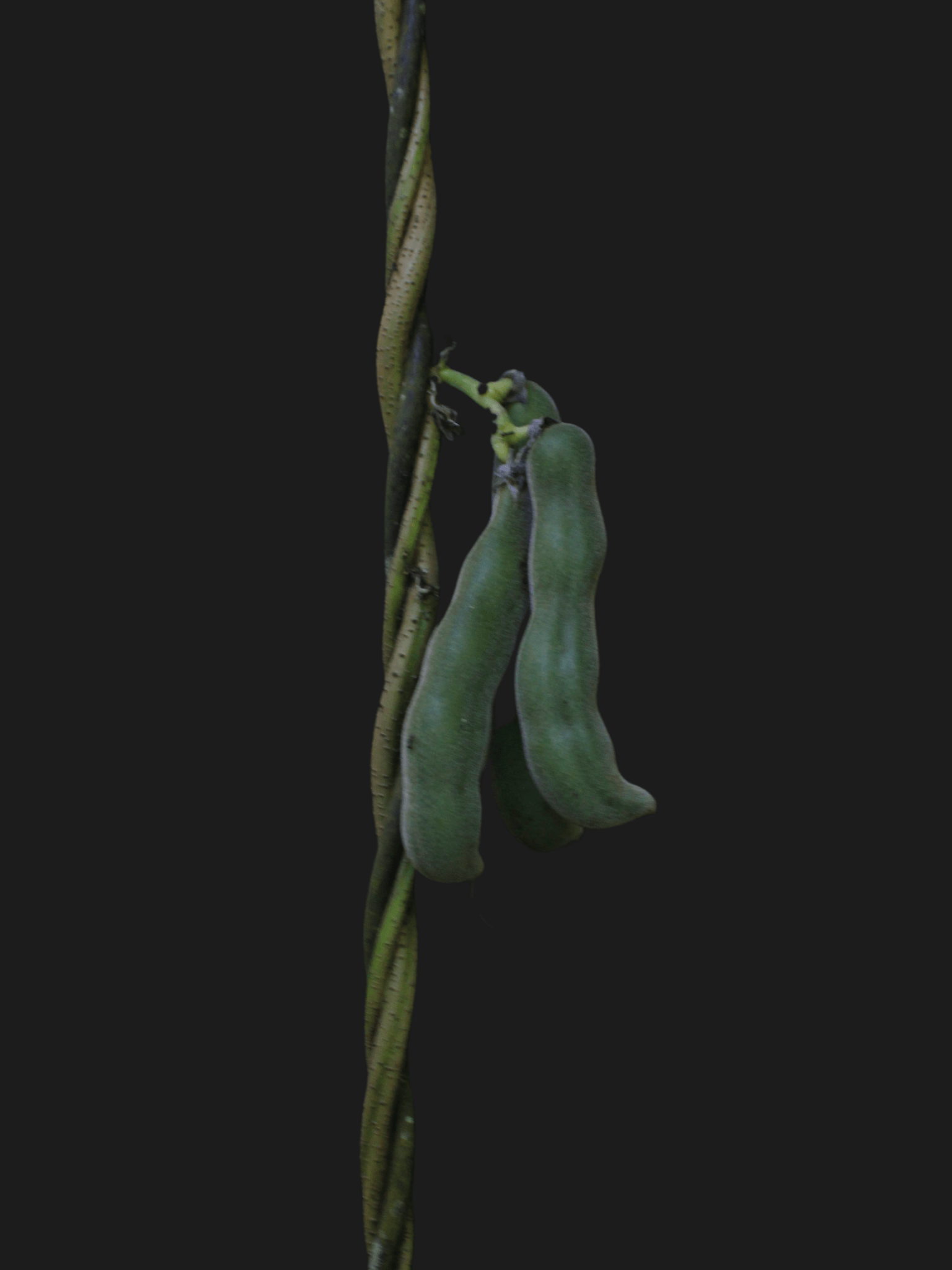

(Photo Sources: Tropis.co)

Indigenous peoples play a vital role in human life. They are the guardians of traditions, culture, and local knowledge that have been passed down for centuries. They live in harmony with nature, protect it in sustainable ways, and possess deep local wisdom about their environment.

During the Kunming-Montreal Conference of Parties in December 2022, the adoption and respect for the local wisdom of indigenous peoples into conservation strategies to prevent biodiversity loss became the first target within the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) goals. In our national life, even the constitution mandates the state to recognize and respect the unity of indigenous legal communities along with their traditional rights, as regulated by law.

However, this global and national respect has not lifted the fate of indigenous peoples from the threats they face. In the last five years, according to the records of the Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (AMAN), there have been 301 instances of land grabs against indigenous territories in Indonesia. A total of 2,578,073 hectares of indigenous land has been seized by the state and corporations. Most of these land seizures were accompanied by violence and criminalization, as they were deemed to occupy concession and conservation areas.

The Conservation Law

Amidst the worsening fate of indigenous peoples, on August 7, 2024, the Government officially enacted Law No. 32 of 2024 on the Conservation of Biological Natural Resources and Ecosystems (KSDAHE). This new legislation, which is an amendment to Law No. 5 of 1990 on KSDAHE, does not specifically regulate indigenous peoples. However, given the many cases of criminalization related to conservation areas and concession lands, there is great hope that the presence of this law will provide better protection for indigenous peoples in relation to conservation.

Unfortunately, although it recognizes the importance of involving indigenous legal communities (MHA) in the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystems, as emphasized in Article 37 paragraphs 3 and 4, this law has yet to provide a meaningful role and guarantee of inclusive space for indigenous communities within conservation areas.

Why? First, instead of further regulating the procedures and forms of involving indigenous peoples in conservation, including specific approaches and respect for the rights of indigenous communities in implementing their local wisdom, the KSDAHE Law refers to another law as the legal basis for such involvement. The law in question is Law No. 32 of 2009 on Environmental Protection and Management (PPLH Law), which has already been integrated into the Job Creation Law.

These two laws do not specifically regulate the roles and rights of indigenous communities as a distinct legal entity that should stand on its own, particularly in the execution of conservation efforts within conservation areas. Instead, these laws merge indigenous communities with the general public under a single term, "community." This is unfortunate because such merging also affects the specific roles and rights that are regulated. It is important to remember that indigenous communities has unique traditional rights that are not held by the general public.

Similarly, in the article regulating ‘preservation areas’—a new term in the KSDAHE law—these are defined as areas outside Nature Reserve Areas (KSA), Nature Conservation Areas (KPA), and conservation areas in waters, coastal regions, and small islands where ecological conditions are maintained. The formation of these preservation areas seemingly refers to the concept of Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECM). However, unlike the OECM concept developed by the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA), which provides governance of protected areas to indigenous peoples or local communities, the preservation areas in the KSDAHE law do not emphasize the regulation of management rights for protected areas to indigenous peoples.

Second, the form of community involvement regulated in the KSDAHE and UUPPLH laws can be described as very passive. Article 70, paragraph 2 states that the community's role in environmental protection and management can include social oversight, giving advice, opinions, suggestions, objections, complaints, and providing information and/or reports. However, in many indigenous communities in this country, they can play a much more significant or active role in conservation through practices based on local wisdom. For example, barong karamaka, leuweung tutupan, leuweung titipan, pangae kapali, sasi lompa, lubuk larangan, awig-awig, and many others.

Third, in the formulation of policies regarding the recognition of the existence of indigenous legal communities, local wisdom, and the rights of indigenous legal communities, the PPLH Law further delegates this authority to provincial and district/city governments. However, not all provincial and district/city governments have the same level of concern for their indigenous legal communities or the same capabilities.

Moreover, for the indigenous communities, obtaining recognition is not easy. The recognition procedure stipulated in the law is very lengthy and, in practice, requires substantial costs. The case of criminalization, such as experienced by Sorbatua Siallagan, the Chief of the Ompu Umbak Siallagan Indigenous Community in North Sumatra in mid-August 2024, stems from the difficulty of obtaining the recognition of customary forests, which, despite having been applied for five years ago, has yet to receive acknowledgment.

Fourth, customary forests versus the principle of state control (Hak Menguasai Negara/HMN) and 'management rights' (hak pengelolaan). The KSDAHE law adheres to the principle of "natural resources belonging to the state." This means that all conservation areas, including customary forests, are under HMN status.

This situation is further complicated by the introduction of the 'management rights' category in the Job Creation Law. 'Management rights' refer to the state's control rights, the implementation authority of which is partially transferred to the rights holders (Article 136 of the Job Creation Law). “Management rights” are granted to several legal entities listed in Article 137, paragraph 1, of the Job Creation Law, namely central government agencies, regional government agencies, land bank institutions, state-owned enterprises (BUMN/BUMD), and legal entities designated by the central government. Article 138 also states that third parties (private sector) can be granted these rights through a 'land use agreement'.

Seven Steps

The 'management rights' regulated by the Job Creation Law do not mention any land control rights for indigenous peoples. This situation further exposes indigenous peoples to criminalization and displacement in conservation areas. Moreover, if their communal forest lands border or overlap with private concession lands, they are increasingly vulnerable to losing in legal disputes.

That is clearly very ironic. According to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007), formal recognition of indigenous land rights is the first critical step for involving indigenous communities in conservation.

Following land rights, six additional steps need to be taken: inclusion in decision-making processes; the integration of traditional knowledge with modern knowledge in conservation policies; a community-based approach; protection of culture and spirituality; long-term funding and support; and joint monitoring and evaluation.

Involving indigenous communities in the conservation of biological natural resources is not a choice but a moral and practical imperative. This is where the state needs to step in by providing fair regulatory guarantees for them through the adoption of just and wise measures.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Opini

ID

ID

EN

EN

Terms and Conditions